Why have I kicked off this Mother’s Day piece with a defeatist tone, you may ask? Because my road to and through motherhood has been a rocky one, and I know I’m not alone. And while my body of photographic work strives to capture snippets of beauty in the mess and chaos of child-rearing, I’m also on a quest to spread truth about the journey, and in turn, do my small part to de-stigmatize the struggles that we face as mothers. After having my first baby (now a kindergartener), I battled severe postpartum depression — I lost the ability to sleep, eat, and care for my child in the way that I had dreamed of for so long — the way that society told me it would surely look like. I cried for weeks on end, suffered from thought patterns that weren't my own, gave up completely on breastfeeding (and hated myself for it), and quite frankly felt as though I needed to escape...permanently. And while all of this was excruciatingly difficult, I found that one of the hardest parts of PPD was that, other than a psychologist and a Brooke Shields book, I had no one in my life at that time who could fully relate, and therefore I was alone and paralyzed with guilt on top of it all.

After months of therapy and meds, my story’s trajectory took a decidedly upward turn, and I eventually found glimmers of light through all that darkness. I poured myself back into photography, and my way of seeing the world shifted completely. I started focusing on telling the stories of families through my lens, spending most of my sessions with new mamas, sharing experiences of complete despondency — and also complete delight — and as such, finding that my reality as a mother looked no different than that of my peers.

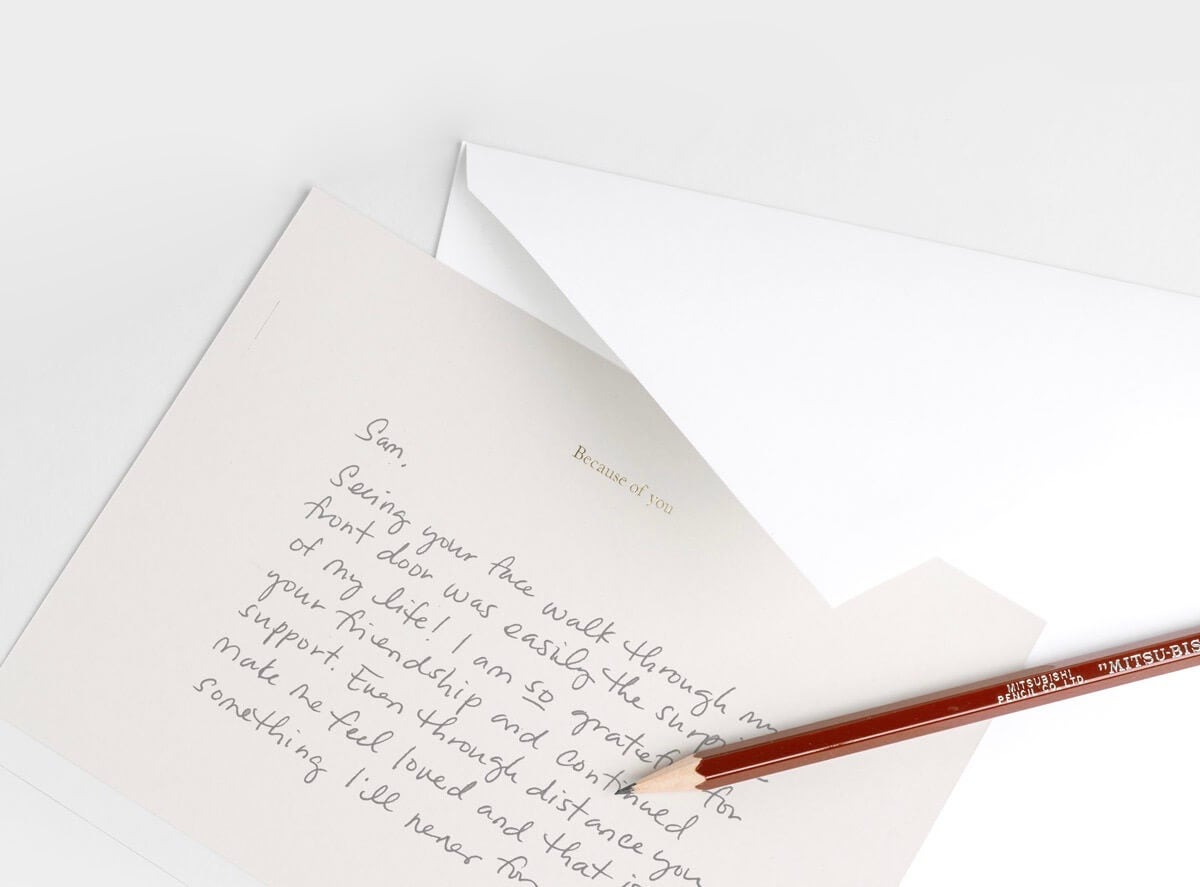

Not until I started connecting with and photographing my mama clients (many of whom became dear friends) did I begin to clearly see for myself slices of joy throughout my own parental path. In essence, creating my work became a survival tool, and to this day I see my motherhood photography as a means to not only frame this wild life in a way that can show mamas how much beauty exists in the breakdown, but also as a conduit for communication.

My career has unexpectedly become a way to spend quality time with my mama peers and reassure them that the visuals of windswept moms in wheat fields with a baby sleeping peacefully in their prairie-dress-clad arms are only a fraction of the full picture—and that there’s complete validity and value in both the final image and the war story that’s most definitely behind it.